One recent, rainy Monday in Milan I was left with the conundrum of what to do… A lot of things in Milan (and Italy in general) are closed on Mondays – history museums, art galleries, special exhibits, restaurants – and the wet weather wouldn’t really allow many outdoor activities. I thought and thought and thought and then finally (as I should’ve done after the first “thought”) pulled out my phone and Googled it. After searching through a bit of fluff (not all blogs out there are as content-heavy as mine – haha) I finally found it, the perfect thing to do on a rainy day in Milan: go to the Museum of Teatro alla Scala!

La Scala is well-known as one of Italy’s – and Europe’s! – premiere opera houses. It was inaugurated on August 3, 1778 and originally called the “New Royal Ducal Theater alla Scala”, as it replaced the Teatro Regio Ducale that had burned down on February 25, 1776, after a carnival gala and was built on the site of the former church of Santa Maria alla Scala (from which it takes its contemporary name). Known popularly as simply “La Scala”, the design of the building by Pietro Marliani, Pietro Nosetti and Antonio and Giuseppe Fe was commissioned by Austrian Empress Maria Theresa and paid for my the generous and enthusiastic support of the former theater’s box owners, who were eager to have another opera house in Milan.

The new La Scala has been honored with premieres by some of opera’s most renowned composers over the past 2035 years, including Giuseppe Verdi, Giacomo Puccini, Gioachino Rossini and Gaetano Donizetti. It also sponsors its own ballet company as well as a music academy. The museum, which I was about to visit, was opened on March 8, 1913, after a group of wealthy Milanese banded together to buy a private collection of Milanese opera memorabilia that was put up for auction by notable collector Giulio Sambone in Paris on May 1st, 1911. After succeeding in acquiring the collection, these notable opera fans donated the collection to the city of Milan for the opening of an opera museum that we now know as the Museo Teatrale alla Scala. Since then, many things have been added to the original collection to include costumes, set designs, autographed musical scores and musical instruments of historical interest as well as paintings of musicians and actors who played at La Scala and a range of random, opera-related objects including precious ceramic figures portraying characters from the commedia dell’arte and board games which used to be played in the theatre’s foyer. There is also an attached library, the Biblioteca Livia Simoni, founded in 1952, which now holds over 140,000 works related to opera and theater.

The entrance to the museum is to the left of the opera house if looking at it from the square outside. At the time of my visit the cost of a full-priced ticket was €7, which I paid to the man sitting to the right behind a glass window and then proceeded up several flights of steps, pausing now and then to read the opera posters lining the walls, until I reached the entrance.

Guests are ushered through the hall of the opera house toward the entrance to the boxes before entering the museum itself. Turning the corner into that grand foyer with its elegant, crystal chandeliers and gold-topped pillars reaching toward high, arched ceilings made me stop in my tracks. Mirrors lining the left wall make the room seem bigger than it is, while beyond the pillars on the right was a narrow space set with red chairs as if for a conference or intimate concert and busts of famous composers watching over things between the windows that look out onto the square.

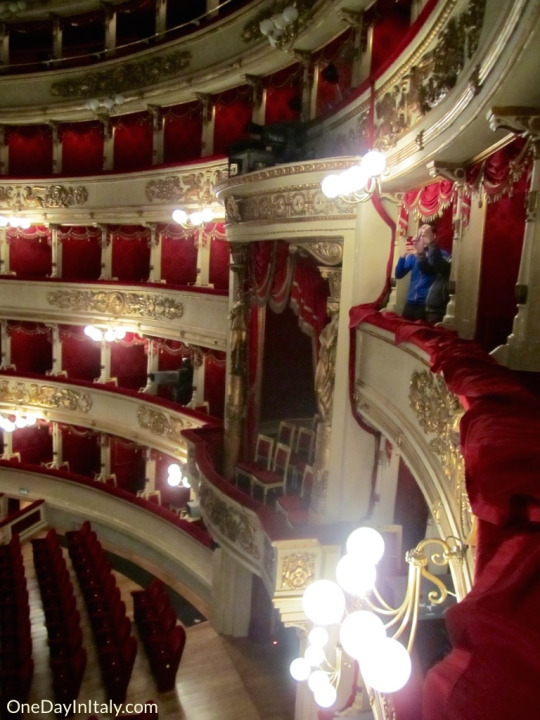

Stanchions guide you to the left, into a narrow, curved hallway with short, numbered doors inset every twenty feet or so. Three of the doors were open. Through the doorway there was a brief “tunnel” and on the other side I could glimpse the most brilliant crimson color, a stark contrast to the creams and crystals of the outer hall.

I walked through one of the doorways and found myself in an opera box! Crimson material lined the walls enhanced by a delicate snowflake pattern. The chairs were crimson, too, as well as the lush valance hanging from the top edge of the box’s window to the stage, its gold tassels matching the gold moldings of the chairs and of the room itself.

Through the opening the entire opera house was laid out before me. To the left and right, up and down, were more and more boxes like the one I was in, but too my right was also a box many times the size of any other. I wondered who sat there… The stage was to my left, one of the largest stages in Italy. And above, a grand and glorious crystal chandelier was the focal point of a beautifully carved ivory ceiling. I spent as much time as I could in the box, imagining sitting there as Turnadot or Otello or Madame Butterfly was played out on the stage in front of me by some of the world’s most renowned opera singers, until I couldn’t stay any longer without feeling ridiculous.

I headed back past the entrance to the stairwell and went the opposite way and into the museum. Now, at this point I have to admit that while I can appreciate opera, I’m not exactly the biggest connoisseur in the world… In fact, you could probably call me fairly ignorant about the history and traditions of opera. The items housed in the museum were, I’m sure, treasured pieces of a long and notable operatic history. There were lots and lots of portraits – some small enough to fit in a wallet and others almost filling a wall – of singers and composers affiliated in some way with La Scala. Sheets and sheets of musical scores, knick-knacks, collectables and personal letters were showcased in glass-covered credenzas. There were busts everywhere, particularly in the last room, and I managed to recognize some names – Puccini, Verdi, Caruso, Maria Callas… It was all very beautiful, but I was able to go through fairly quickly, as much of it didn’t hold any real significance for me.

This piano caught my eye, though. It was a gift from Steinway & Sons, the world-famous piano manufacturer, to Hungarian composer Franz Litz in 1883. Later, Litz’s granddaughter brought it with her when she bought a villa on Lake Garda. Unfortunately the villa was requisitioned by the Italian State (and the piano with it), renamed “Il Vittoriale” and given to poet, war hero and friend of Mussolini Gabriele D’Annunzio. I had visited Il Vittoriale two years past, which is why this story caught my attention. After D’Annunzio’s death, Litz’s granddaughter launched into a long legal battle for possession of the piano, which she eventually won. But what did she do with it once it was back in her possession? Quickly made it leave her possession once again when she donated it to Museo Teatrale La Scala!

I wouldn’t say my visit to La Scala’s museum took much more than an hour, but it was a nice little piece of Milan’s history to explore on a rainy, Monday afternoon. It also inspired me to buy an opera ticket on one of their “ScalAperta” shows (”Open Scala” shows are once per season per show and tickets are half-price). Unfortunately, I picked a modern opera that had been staged especially for Expo and HATED it! Next time I’ll definitely opt for a traditional opera or ballet; the “here are some words, sing whatever you want as long as it doesn’t sound like a song” sort of modern operas are simply not for me!

Find out more about Museo Teatrale La Scala, including current admission prices and opening times, on their website: Museo Teatrale La Scala.

Comments

comments

Leave a Reply