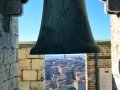

When I was in Florence last year I joined hundreds of tourists in the square who were admiring the beauty of the Duomo, Santa Maria del Fiore. It was only when I returned to the States, though, that I read Ross King’s bestseller “Brunelleschi’s Dome: How a Renaissance Genius Reinvented Architecture”. I have to say, I was expecting a novel. A novel based on fact, but still a novel. Instead, the book reads like one big essay, going into great detail on the construction of the dome and the associated lifts, tools, materials and mechanisms that Filippo Brunelleschi created to complete this historic achievement.

“What’s the big deal?” you say? “There are domes all over Europe!”

Yeah, that’s what I said, too. But 120 years after the construction on Santa Maria del Fiore had begun in 1296AD, no one had yet figured out a way to construct the dome without flying buttresses (which the Wool Merchant Council in charge of the project refused to use; flying buttresses were the fashion in Milan, at that time an archenemy of Florence). They weren’t sure that there would even be enough wood of the right quality and proportions available in Tuscany to build scaffolding for the dome, considering it would have to be built 180 feet above the ground. They were also concerned that a dome as high and wide as the dome in architect Arnolfo di Cambio’s original design wouldn’t be able to support itself once it was finished, that it would fall crashing to the floor under the pressure of its own mass (di Cambio had envisioned the dome but hadn’t known how it would be realized).

The Council of Wool Merchants decided to hold a contest for the commission of the Dome, as was the popular trend for a project of any scope or that required any level of talent. Architects and artisans flocked for Florence to build their models, including the surly-tempered Brunelleschi and his fellow goldsmith Lorenzo Ghiberti, who had for some time been one of his chief rivals. Ghiberti had recently beaten out Brunelleschi for the commission to create the now-infamous bronze doors of Florence’s Baptistery.

Filippo’s design seemed ingenious, in part for its mystery. His proposal was to build two domes, both without scaffolding: a lower, inner dome that would be viewable from inside of the church and a taller, wider outer dome that would give Florence’s skyline the impressive stature that di Cambio had originally envisioned. But Filippo was a secretive man, paranoid – or perhaps rightly concerned – that his competitors would steal his ideas if he wrote them down or made them known, so his plan did not give specifics on exactly how he would build the dome. After many arguments with the Wool Merchants Council, Brunelleschi was finally awarded the commission (though without the prize of 200 gold florins that had been promised) with one caveat: He would have to share the job of capomeastro, or construction superintendent, with his rival Ghiberti.

Over the decades that followed, Brunelleschi won several other commissions having to do with the dome, including an incredibly complex design for a machine to lift the huge, heavy slabs of stone and marble from the floor of the Duomo up 200 feet and put them in place. He also designed the “lantern”, the piece that tops the dome and gives it its extra height, though he never got to see it completed.

A few months after the base for the lantern was installed in 1446AD, Filippo Brunelleschi died of a sudden illness. The cathedral had been consecrated by Pope Eugenius IV on the Feast of the Annunciation in 1436 and now the dome’s architect would be one of the few honored deceased to be buried in the crypt underneath Santa Maria del Fiore. Architects, in Brunelleschi’s time, were considered little more than skilled craftsmen, but the memorial plaque on his tomb proves how much Filippo served to advance his profession in the eyes of the populace. The plaque’s inscription honoring his “divine intelligence” shows that the one-time goldsmith became much more, that his creativity and ingenuity in both the construction of the dome and the machines he invented to build it were recognized and respected as extraordinary even during his own time.

Comments

comments

Leave a Reply